My First Teachers

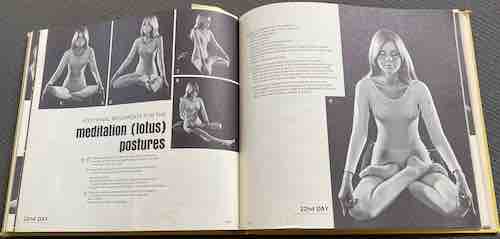

One’s parents are one’s first–and hopefully best– teachers. From my father I acquired a love of science and mathematics. My mother took up Yoga in 1971 when I was eight years old. (I remember thumbing through her copy of Richard Hittleman’s Yoga: A 28-Day Exercise Plan and trying out the postures, imitating what I imagined to be the practices of sages in the mountains and forests of Eastern lands.) Together the two of them fostered a home-environment that was perhaps unusual among Southern familes of that generation: rationalist, humanist, and religiously free-thinking, albeit with a slight New Age twist.

One’s parents are one’s first–and hopefully best– teachers. From my father I acquired a love of science and mathematics. My mother took up Yoga in 1971 when I was eight years old. (I remember thumbing through her copy of Richard Hittleman’s Yoga: A 28-Day Exercise Plan and trying out the postures, imitating what I imagined to be the practices of sages in the mountains and forests of Eastern lands.) Together the two of them fostered a home-environment that was perhaps unusual among Southern familes of that generation: rationalist, humanist, and religiously free-thinking, albeit with a slight New Age twist.

A dream that I experienced several times as a child expresses the interplay between Reason and Mystery that my parents hoped I would grow up to explore:

Early in the morning, when it is still quite dark, I slip out of the house, having resolved to explore “to its very end” the forest that borders our backyard. In time, as dawn gives way to morning, I leave behind the gentle rolling pine-needled hills of the Carolina Piedmont and the terrain becomes progressively steeper: I am walking up a mountain that is completely embedded in this forest. At the ridge-top the forest ends abruptly: the downward slope is all grassy meadow, and glistens under the late-morning sun. A great stone city fills the valley below. Moss and ivy overgrow its dwellings, courtyards, and fountains, giving an impression of deep antiquity. Yet the city is well-populated and pulses with quiet, intense life. Its inhabitants are clad in wizard-robes, and they are of two types: Scientists and Sages. The Scientists fashion large spherical crystal balls; the Sages peer into them.

Encountering the Practice

I will always be grateful to Deirdre Smith Gilmer for showing me and a few colleages the Primary Series when we taught together in the summer of 1998 at the North Carolina Governor’s School. At that time Deirdre was a student of Eddie Stern in New York City. Eddie in turn was a student of Sri K Patabhi Jois of Mysore, India.

Further Studies

Like many other serious students of Aṣṭāṅga, I soon became interested in the history of the practice and in the Indian philosophical systems and religious communities in which Yoga developed. While on sabbatical in the 2002-2003 academic year I had the good fortune to begin the study of Sanskrit with Christopher Minkowski. Originally a specialist in Vedic ritual studies, Chris was beginning to look into the history of mathematics and related knowledge-systems in pre-British India. From time to time the two of us would meet to translate passages from the Lïlāvatī, a classic Sanskrit mathematical text: Chris would help me with the language and I would explain the mathematical concepts to him; it was a lovely exchange. Sanskrit got me doing my own small-scale work in the history of Indian mathematics; in this regard I benefitted very much from the advice of another academician, the American historian of mathematics Kim Plofker.

Like many other serious students of Aṣṭāṅga, I soon became interested in the history of the practice and in the Indian philosophical systems and religious communities in which Yoga developed. While on sabbatical in the 2002-2003 academic year I had the good fortune to begin the study of Sanskrit with Christopher Minkowski. Originally a specialist in Vedic ritual studies, Chris was beginning to look into the history of mathematics and related knowledge-systems in pre-British India. From time to time the two of us would meet to translate passages from the Lïlāvatī, a classic Sanskrit mathematical text: Chris would help me with the language and I would explain the mathematical concepts to him; it was a lovely exchange. Sanskrit got me doing my own small-scale work in the history of Indian mathematics; in this regard I benefitted very much from the advice of another academician, the American historian of mathematics Kim Plofker.

Teaching

Aspirations

Over the years I have taught Aṣṭāṅga in the form of a physical education course at the small liberal arts college where I teach, and privately to individuals who have expressed an interest in it. Aṣṭāṅga has been the cornerstone of my physical health, has inspired a series of studies that deepened my appreciation of the humanities, and has been for me the gateway to meditation and other forms of spiritual practice. Nearing the end of my career as a mathematics professor, I aim to devote more time to passing on this Yoga as freely as possible, following the example of Deirdre, Chris and Kim, each of whom taught me for free, out of love for their own disciplines.

Over the years I have taught Aṣṭāṅga in the form of a physical education course at the small liberal arts college where I teach, and privately to individuals who have expressed an interest in it. Aṣṭāṅga has been the cornerstone of my physical health, has inspired a series of studies that deepened my appreciation of the humanities, and has been for me the gateway to meditation and other forms of spiritual practice. Nearing the end of my career as a mathematics professor, I aim to devote more time to passing on this Yoga as freely as possible, following the example of Deirdre, Chris and Kim, each of whom taught me for free, out of love for their own disciplines.

Keeping It Simple

Although not designed specifically as a form of exercise, Aṣṭāṅga is nonetheless a relatively vigorous form of Yoga, and for a time during its transmission to Western countries it acquired an undeserved reputation as a rigid and overly-demanding activity, to be restricted to the most “talented” practitioners only. But in fact Aṣṭāṅga is meant to be moulded according to the needs of the practitioner: not the other way around! So feel free to ignore the elaborate postures in the images here: they exist mostly to give ambitious young folks something to fool around with! Whether one’s postures are “elementary” or “advanced”, real Yoga lies in the association of breath with movement—movement that is as simple and undemanding as it needs to be.

Note on Lineage

My most extensive formal training in Aṣṭāṅga is from Andrew Eppler in the form of a 200-hour Intensive Training, in virtue of which I am registered with the Yoga Alliance as a teacher. I continue to study with Andrew, residing periodically at his shala in Oklahoma.

My most extensive formal training in Aṣṭāṅga is from Andrew Eppler in the form of a 200-hour Intensive Training, in virtue of which I am registered with the Yoga Alliance as a teacher. I continue to study with Andrew, residing periodically at his shala in Oklahoma.

Andrew is the primary American student of BNS Iyengar of Mysore, India, who in turn was a student of both Patabhi Jois and Jois’ own teacher, Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya. It was Krishnamacharya who developed the Aṣṭāṅga Vinyāsa Yoga system while teaching at the Mysore Palace School (1931-1948).